Mannheim Tax Index

Tax Attractiveness in Europe

The Mannheim Tax Index is an indicator for the effective tax levels of companies, as taxation is deemed to be an important location factor. More precisely, it benchmarks countries and regions from a tax perspective, taking into account taxes on profits and invested capital as well as the most important regulations in determining the taxable base. In doing so, it provides a comprehensive picture of taxation by following two general strands: the taxation of domestic companies along with their shareholders and cross-border corporate investments. Analysing the taxation of companies is a traditional way of comparing the fiscal attractiveness of regions competing with one another internationally. It concentrates on the tax rates borne by mobile capital and mobile companies.

Dr. Daniela Steinbrenner

ZEW ExpertOur index is based on effective tax burdens for two reasons: They are more relevant for investment decisions than nominal tax rates, and their aggregate level makes them directly comparable across locations. Looking at these effective tax rates over time provides intuition about common trends in tax competition and possible interdependencies between locations.

Tax Location Attractiveness

In 2025, the economic situation in Europe remains tense. Although there are overall signs of a slight economic recovery in the EU, significant differences persist between Member States. In particular, the large Member States such as Germany, France, and Italy are struggling with especially low growth rates and a significant decline in their potential growth. To counteract this development and create new, long-term economic growth, it is crucial, among other things, to strengthen corporate investment activity. In addition to direct support instruments such as grants, low-interest loans and state venture capital, tax incentives as an indirect support instrument are becoming increasingly important in economic policy considerations. They can provide targeted investment incentives and thus make an important contribution to new economic growth.

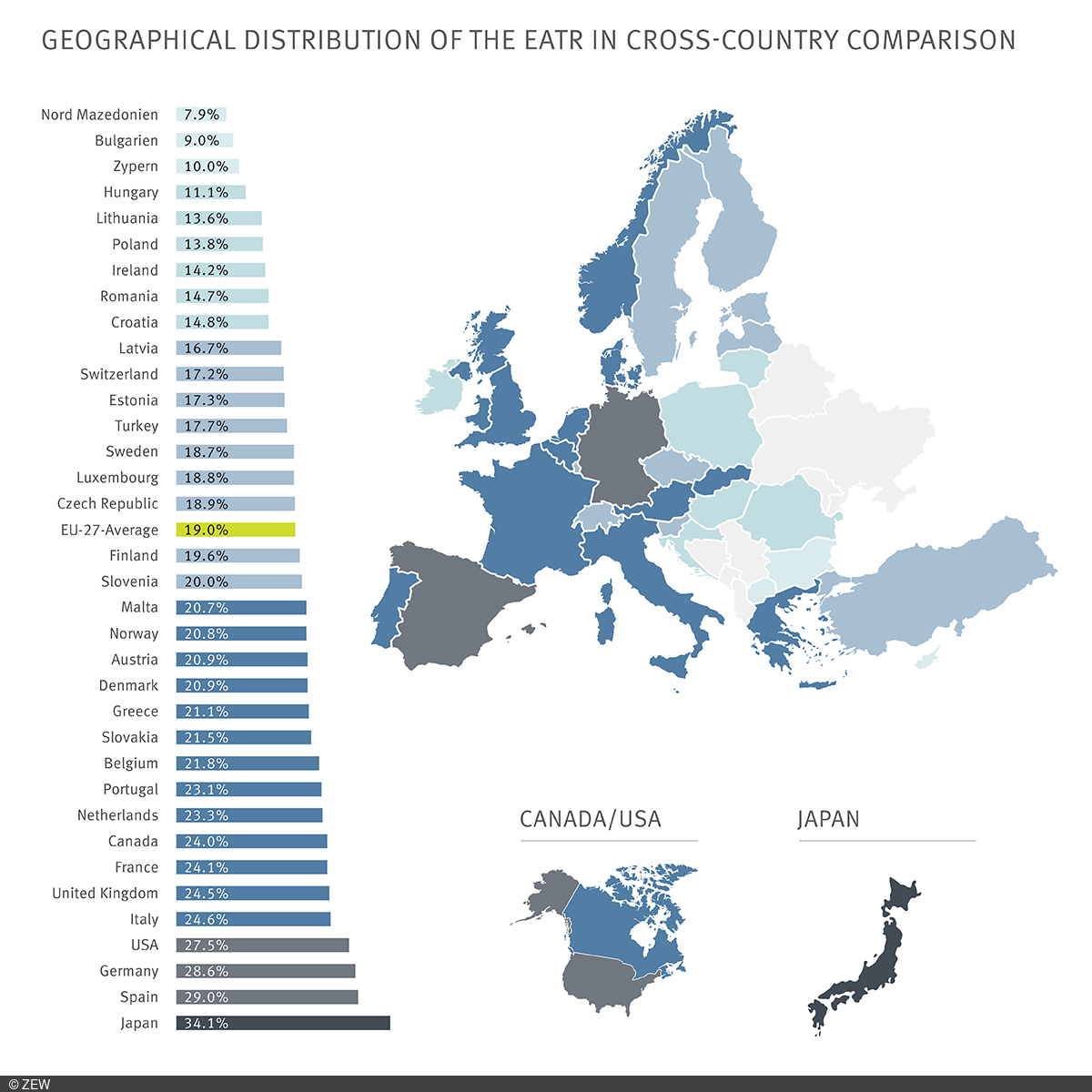

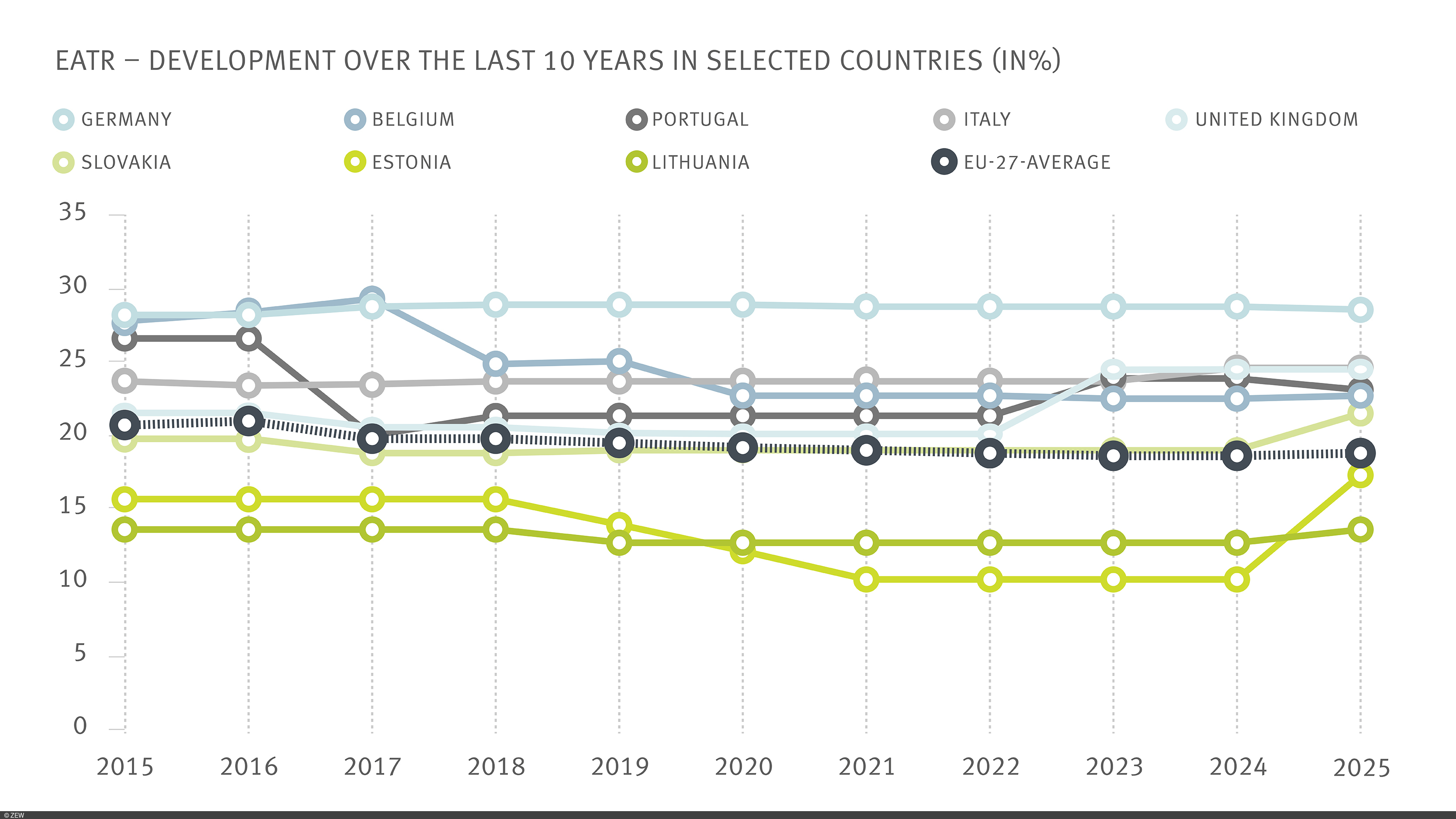

The tax location attractiveness, measured by the effective average tax rate (EATR), has changed little compared to previous years, particularly in low- and high-tax locations. Changes in the mid-range of the country ranking can be attributed primarily to adjustments in the corporate tax rate, which is often used as a tool for tax incentives for investment. The time series shows, however, that tax rates are currently tending to converge. In particular, in several Central and Eastern European countries, tax rates are rising and increasingly approaching the European average. Following last year's increases in Slovenia (from 19% to 22%) and the Czech Republic (from 19% to 21%), further Member States are following suit with corresponding reforms this year. Estonia is raising its general corporation tax rate from 20% to 22% and abolishing the reduced rate of 14%. Lithuania is raising its tax rate from 15% to 16%, while Slovakia is implementing a significant increase from 21% to 24%. This development signals a shift away from aggressive tax policies aimed at creating location advantages and investment incentives based on reduced tax revenues. The main reason behind these measures is to strengthen public finances in the face of various crises (including the COVID-19 pandemic, the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine). This also leads to a slight increase in the overall effective average tax burden within the EU.

This development marks a shift away from aggressive tax policies aimed at creating location advantages and investment incentives based on reduced tax revenues. Against this backdrop, Germany's planned reduction of the combined corporate tax rate from around 30% to 25% by 2032 can be seen as a promising step towards restoring its tax competitiveness. Germany would move closer to the average again without getting caught up in a ‘race to the bottom’. At the same time, moving closer to the average tax burden is sensible given that Germany has recently seen a decline in competitiveness in key location factors such as infrastructure, educational attainment, energy prices and bureaucratic burdens.

Cost of Capital in High-Tax Countries

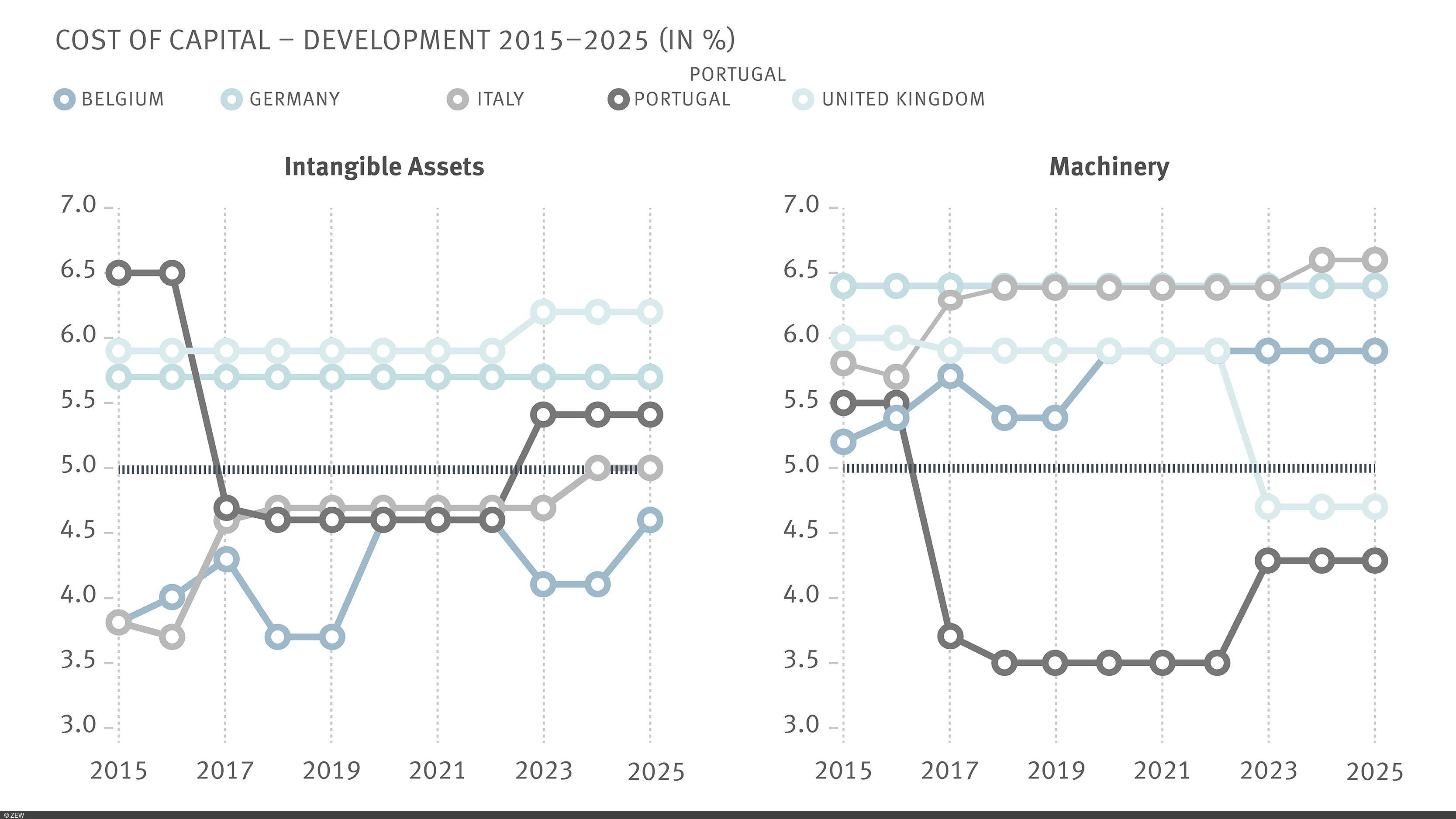

Several of these Central and Eastern European countries are accompanying their moderate tax increases – which have little impact on their location attractiveness for businesses – with targeted investment incentives through tax base adjustments. Such indirect tax incentives are particularly targeted and have a stronger effect with higher tax rates. While indirect tax incentives often have less of an impact on the effective average tax rate, which reflects the tax location attractiveness in international comparison, than tax rate reductions, their effects are much more visible in the cost of capital. The cost of capital indicates the minimum pre-tax return an investment must generate to be economically viable after tax compared to an alternative investment. Lower capital costs signal a lower minimum pre-tax return, making it more attractive to expand the volume of investment at a given location. The cost of capital is interpreted in relation to the return on the alternative investment. Here, a hypothetical financial investment that generates a return equal to the assumed market interest rate of 5% is assumed: if the cost of capital is below the real market interest rate, the corporate investment is more favourable from a tax perspective than an alternative investment on the capital market.

A comparison of various high-tax countries reveals considerable variation in the cost of capital, which is primarily due to specific investment incentives. These include, in particular, the notional interest deduction on equity (e.g. Belgium until 2022, Italy until 2023, Portugal) to reduce the debt equity bias, and increasingly incentives in the form of accelerated or excess depreciation. Accelerated depreciation results in a tax advantage due to the tax deferral effect. Over the past ten years, the average cost of capital for acquired patents in Italy was 4.6% and the average cost of capital for machinery in Portugal was 4.1%. Similarly, despite increasing its corporation tax rate from 19% to 25% in 2023, the United Kingdom was able to reduce its cost of capital to 4.7% by simultaneously introducing full immediate depreciation for machinery. In addition, some countries offer opportunities for excess depreciation, whereby amounts above the actual acquisition costs can be deducted for tax purposes. As a result, Belgium has achieved an average capital cost of 4.2% for acquired patents over the past ten years. At the same time, these regulations lead to distortions between different economic goods: in Belgium and Italy, intangible assets are significantly more tax favoured than tangible assets, while in Portugal and the United Kingdom, the opposite is true. Such differences can lead to undesirable disincentives and market distortions.

The previous examples show that, even with corporation tax rates above the EU average, investment incentives can be advantageous from a tax perspective, expanding investment volume can be advantageous from a tax perspective, as corporate investments benefit from tax incentives compared to alternative investments on the capital market. Germany, in contrast, does not currently offer comparable investment incentives for large companies. Accordingly, the cost of capital for acquired patents at 5.7% and for machinery at 6.4% is significantly above the real market interest rate of 5%. In order to create new investment incentives, the German government has announced a degressive depreciation of up to 30% for movable fixed assets as part of its ‘growth booster’ for the years 2026 to 2028. This accelerated depreciation would reduce the cost of capital for machinery to 6%. This, however, is not enough to make corporate investments significantly more attractive than capital market investments from a tax perspective. Due to the high starting level, for example, only a complete immediate write-off based on the UK model could reduce the cost of capital for machinery to up to 4.7%. The unilateral promotion of tangible assets carries the risk of additional market distortions and requires further political action, for example through expanded tax incentives for output of R&D. In summary, stronger input-based tax incentives in combination with the emerging tax level of 20-25% in the EU offer Germany a good opportunity to strengthen its international competitiveness and at the same time stimulate the expansion of domestic investment.

Devereux-Griffith Model

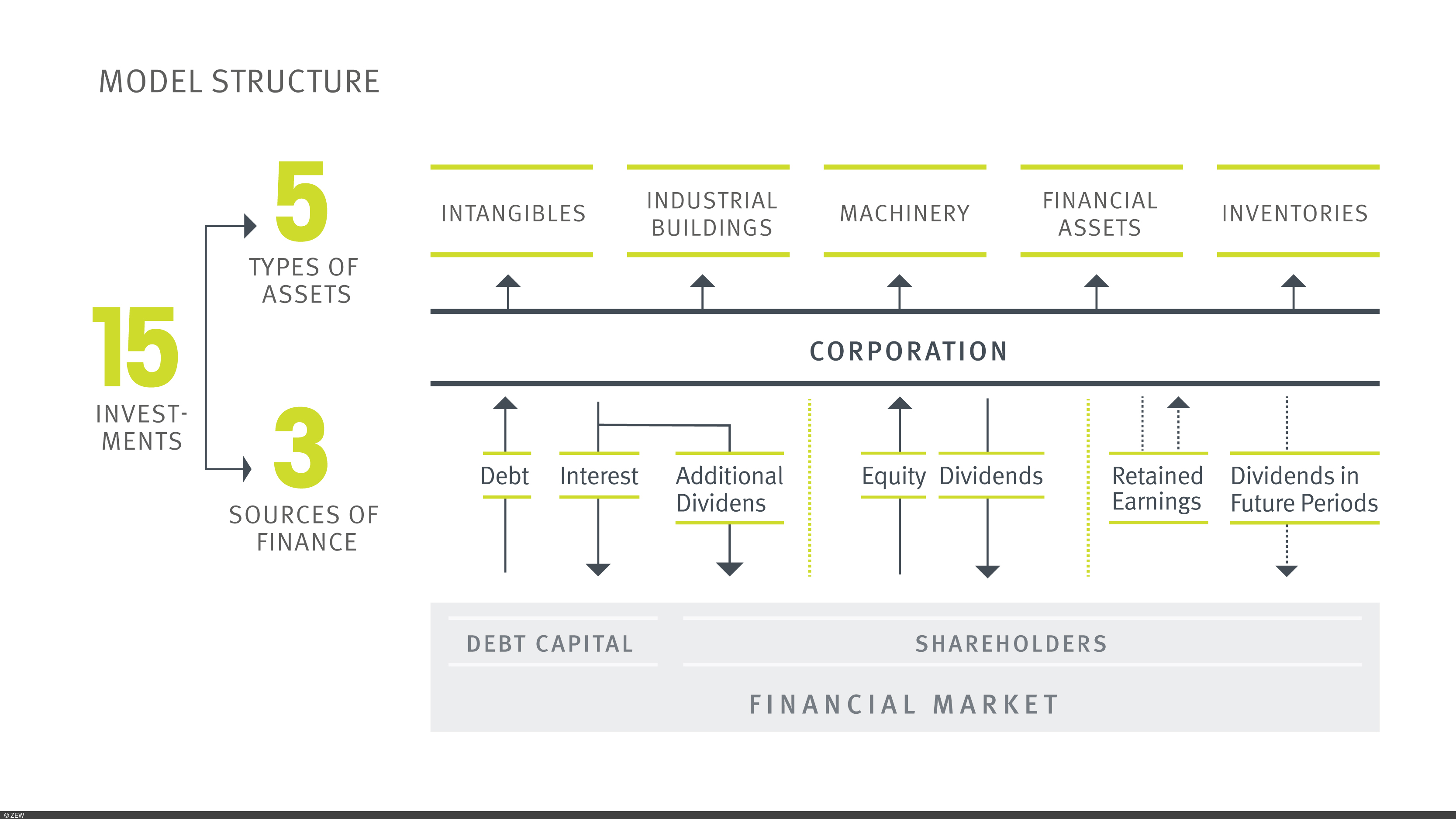

The calculation of the Mannheim Tax Index is based on the established investment theory approach by British economists Devereux and Griffith (1999, 2003). By taking into account several tax parameters and their effects on a hypothetical future investment, the effective tax burden of a country is calculated and tax-induced distortions in the choice of location are shown. Both the cost of capital and the effective marginal tax rate of a marginal investment, which influence the scope of investment at a specific location, as well as the average effective tax burden on a profitable investment, are calculated.

The “Model Structure” chart shows the structure of an investment and its financing. The calculation of the Mannheim Tax Index is based on a corporation in the manufacturing industry which invests in a specified combination of various assets either through itself or a foreign subsidiary. The hypothetical investment project consists in equal parts of intangible assets, industrial buildings, machinery, financial assets and inventory. Various forms of financing are also taken into account. Financial sources in order of their weighting are retained earnings, borrowed capital and new equity capital.

Data

Please cite the data as:

Heckemeyer, J., Nicolay, K., Gaul, J., Gundert, H., Raabe, R., Schmid, A., Spix, J., Steinbrenner, D., Wickel, S. (2025), Mannheim Tax Index Update 2025 - Effective Tax Levels using the Devereux/Griffith Methodology, MannheimTaxation Project, Mannheim.

Access to Data:

The Mannheim Tax Index calculates effective tax rates for 27 EU countries as well as the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, North Macedonia, Turkey, the USA, Canada and Japan for the period from 1998 to 2025. In addition to the company level, the shareholder level and cross-border bilateral investments are also covered. The information is available for download: