Decline in Research Productivity Harms Economic Growth

ResearchR&D in China and Germany

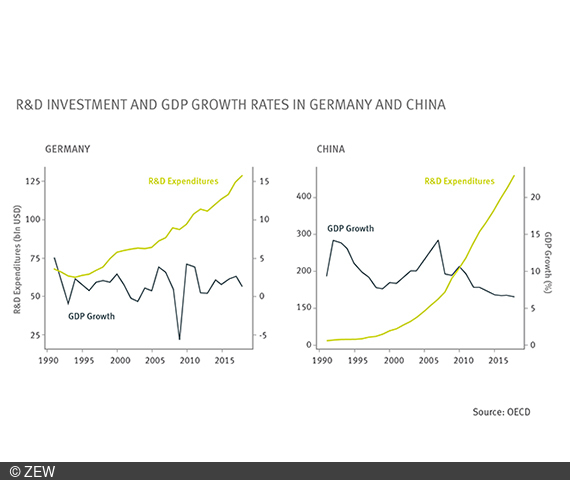

Expenditure on research and development (R&D) has increased significantly in Germany and China in recent years. The resulting output growth is, however, lower than expected in both countries. “This indicates that research productivity in both economies is too weak,” explains Dr. Philipp Boeing, senior researcher and China expert at ZEW Mannheim. In a ZEW policy brief published today, he and Paul Hünermund, PhD, assistant professor at the Copenhagen Business School, have analysed how investment in R&D is related to research productivity in Germany and China. They conclude that in order to achieve sustained growth rates in Europe, “an innovation policy is needed that takes a bottom-up approach and does not rely too heavily on mission-driven research policies. This is the only way to achieve breakthrough innovations that can compete globally with the leading industrialised countries. China’s strongly mission-driven innovation policy cannot serve as a role model in this regard.”

A country’s research productivity measures the efficiency with which R&D investments are translated into output growth through innovative products, processes and services. Research results on the US have confirmed that a decline in research productivity at the global technology frontier is the key reason for sluggish growth.

In order to determine how pronounced the phenomenon of declining research productivity is in Germany and China, the researchers used company data of both countries from the last three decades to compare company growth with R&D investment. “If research productivity remains constant, firm growth and R&D spending should roughly develop proportionally,” explains Hünermund. “However, our research findings for Germany and China show that this has not been the case.” In Germany, research productivity has fallen on average by 5.2 per cent per year over the past 30 years, while R&D spending has increased by about 3.3 per cent annually over the same period.

Rapid decline in China’s research productivity

The study shows an even clearer discrepancy for China. Investments in research there have increased by 21.9 per cent since 2001, while at the same time the Chinese economy has recorded a 23.8 per cent decline in research productivity. “In comparison to high-income countries such as the USA and Germany, China has undergone an even larger decrease in research productivity over the last two decades,” says Boeing. “However, due to China’s more dynamic economic development we caution against a simple extrapolation of growth rates into the future.” He emphasises though that China needs further growth and that Chinese policymakers are willing to promote it. In this context, however, it is important for the Chinese government to create the right incentives for increased research activities, but to avoid overly mission-driven innovation policies. If policy priorities are driven by national security instead of economic consideration, the Chinese economy runs the risk of a further rapid decline in research productivity.

With regard to the European Union, the results of the study suggest that the increasingly mission-driven, sometimes unambitious research policy should be viewed critically. According to the study, it is essential that R&D becomes a top priority in EU policymaking again. “Fighting the trend of slowing growth and declining research productivity requires the EU to further internationalise its policy initiatives, invest more into education, and secure the availability of a sufficient level of public R&D support over the business cycle,” stresses Hünermund. “Otherwise technological progress and global competitiveness are likely to diminish in the not too distant future.”