Eurozone Reform Under the Microscope

ZEW Lunch Debate in BrusselsThe current debate over the reform of the European Union has come to a head. The European Commission has proposed creating the office of a European Economy and Finance Minister with the aim of streamlining the many complex and fragmented decision-making processes within the European Monetary Union. This and other proposals would, however, likely require the EU Member States to relinquish further sovereignty rights to the EU. How can these reform plans be successfully implemented and what will the Eurozone look like in the future? Does the idea of a European Finance Minister have potential and what obstacles might stand in its way? These are just a few of the questions addressed at the ZEW Lunch Debate “Reforming the Eurozone: Prospects and Challenges”, an event organised by the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW), Mannheim, in collaboration with the research network EconPol Europe. The event, held on 2 May 2018 at the Representation of the State of Baden-Württemberg to the European Union in Brussels, brought together experts from the worlds of politics and research to discuss this pressing issue facing Europe.

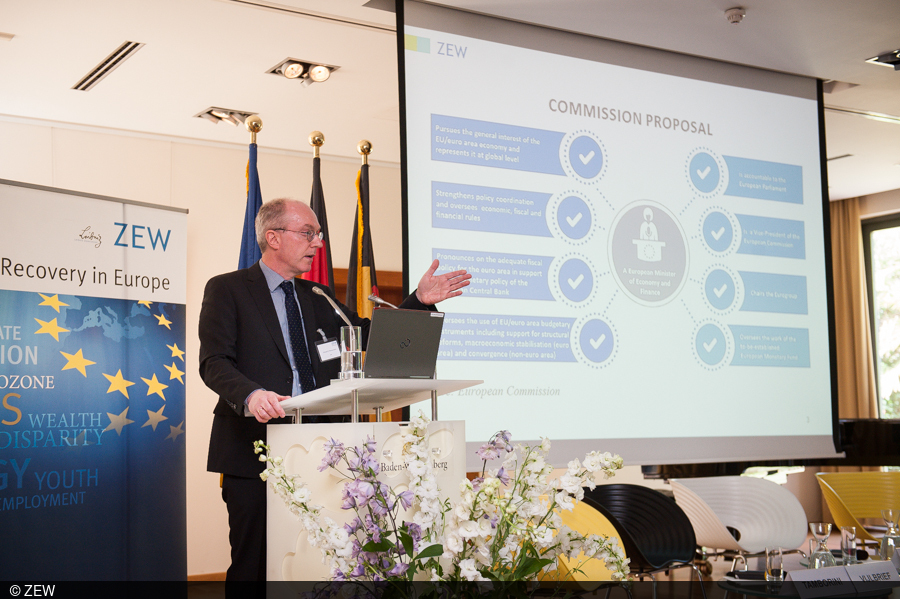

Following an opening address from the head of the Baden-Württemberg State Representation, Bodo Lehman, Professor Friedrich Heinemann, head of the ZEW Research Department “Corporate Taxation and Public Finance” presented the findings of a recent study looking at the role of a European Minister of Economy and Finance within a European Fiscal Union. According to the proposal put forward by the European Commission, the minister would function as both vice-president of the Commission and President of the Eurogroup and assume sweeping responsibilities related to taxation and coordinating Europe’s finances.

The focus of the ZEW and EconPol analysis is to determine whether such a minister with these responsibilities could help Europe to find appropriate solutions to specific challenges facing the fiscal union. Having examined four separate dimensions – fiscal sustainability, macroeconomic shocks, incentives for structural reform and the optimal provision of European public goods –, Heinemann declared it unwise to make creating a European Finance Minister a priority on the EU’s agenda at the present moment. Though such a political office would have some limited positive effects in relation to stabilisation policy and structural reforms, there are at the same time too many drawbacks and unanswered questions in that regard. Particularly in terms of European public goods and fiscal sustainability, a European Finance Minister would not bring any added value to the EU and would instead only be counter-productive. Moreover, combining all these responsibilities into a single institution and a single person could lead to both complementarities and conflict. Assigning too many responsibilities to just one person could also create a bottleneck effect. From a political point of view, a minister with such a broad remit would be a powerful political figure who would likely be met with resistance from the Member States.

Political consensus is difficult to reach

Following his lecture, Friedrich Heinemann was joined on the podium by Paulina Dejmek-Hack, economic adviser to the President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker, Hans Vijlbrief, chair of the working group “Eurogroup” at the Council of the European Union, and Professor Roberto Tamborini, professor of political economy at the University of Trento, for a panel debate. The debate was moderated by the journalist Silke Wettach, EU correspondent at the news magazine “Wirtschaftswoche”. The panel were in agreement that the proposed creation of a European Finance Minister represented only a minor part of a plan for a number of concrete measures from the Commission with the aim of strengthening the European Economic and Monetary Union. The proposal of a new office could then come back on the agenda once underlying issues and structures have been sorted out. As Paulina Dejmeck-Hack pointed out, putting together a sweeping reform package is no straight-forward process. For this reason, instruments for strengthening the Economic and Monetary Union should not be considered separately, but rather as an integral part of the financial structure of the EU as a whole. According to Dejmeck-Hack, the Commission has already taken necessary steps to further strengthen this structure, singling out one of the key concerns with regard to the completion of the banking union, the highly controversial European deposit insurance scheme (EDIS), as particularly important.

Hans Vijbrief also took an optimistic view of the progress made so far. He expects “concrete decisions” regarding the future of the Monetary Union to be made in June 2018, as well as potentially a new timetable and clear conditions for further European integration. He called for decision-makers to view gradual progress, rather than individual political victories, as their main goal. Roberto Tamborini was also in favour of gradual progress, highlighting the role that research can play in identifying alternative strategies. Past experience has shown that the institutional design of Europe’s financial architecture as it stands does not work; therefore, precautionary changes must be made that have both a stabilising effect and are sustainable. Tamborini identified this as an area where a European Finance Minister could act as a catalyst. That being said, such a position would need to be integrated seamlessly into the new reform package.

Many of the 170 guests, who included representatives from the EU Commission and European Parliament as well as participants from the fields of academia, industry and NGOs alongside members of the public, engaged actively in the debate, making suggestions and challenging the panellists’ positions. Their questions included: How can we balance out the differences between the Member States? How important is the social dimension of the Eurozone and what are the risks associated with macro-social disparity? If we have a European Monetary Union, don’t we ultimately need a common economic policy? These are all questions which highlight the need for a more in-depth examination of the proposed reforms as well as their potential effects and anticipated challenges.