Living Lab Could Help Fix Flaws in Contact-Tracing App

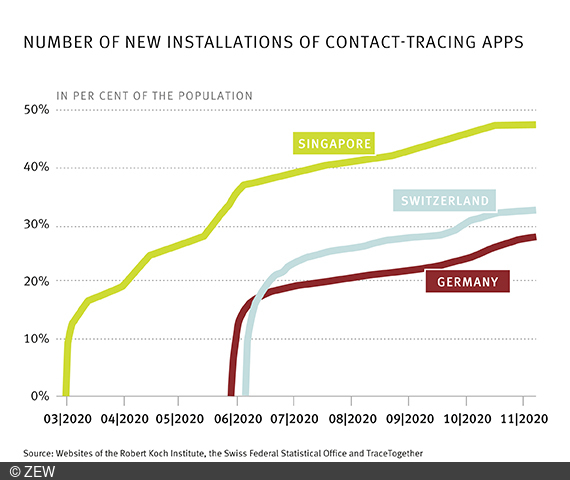

ResearchThe German digital contact-tracing app “Corona-Warn-App” is designed to facilitate and speed up the tracking of SARS-CoV-2 infections. However, the app does not currently meet this objective. “To have its full impact, the app needs to be more widely used and the user guidance needs to be much more geared towards effectiveness. In addition, the app would have to be continuously improved on the basis of a well-defined performance measurement,” says Dr. Dominik Rehse, head of the Junior Research Group “Digital Market Design” at ZEW Mannheim. In a recently published ZEW policy brief, he and a researcher from the University of Mannheim recommend setting up a living lab for the contact-tracing app. The lab should serve to systematically test the measures to promote the app’s dissemination, optimise its use and measure its success in order to significantly improve the app.

The authors recommend that within the framework of the living laboratory, the Robert Koch Institute as the publisher of the app, participating service providers as well as health authorities and scientists from different disciplines should work closely together. The aim is to identify measures that effectively improve the app. However, since changes to the app can have very different effects depending on the user group and the development of the pandemic, they should be tested in actual living environments before their widespread implementation, something that would be possible in the living laboratory. “Unfortunately, the contact-tracing app has not played a significant role in combating the pandemic so far. We need to change that. This requires enabling a clear measurement for success, according to which the app should be systematically tested and optimised,” says Dr. Dominik Rehse.

Living lab offers realistic test environment

The catalogue of proposed measures for improving the dissemination of the app is long. The measure to subsidise the purchase of modern smartphones seems particularly worthy of testing. Furthermore, giving social recognition to the users of the app could also have a positive effect. The measure to facilitate access to public spaces for users of the app seems promising as well. For example, guests at restaurants or cultural events could register with the app via a QR code provided by the organiser instead of writing their name on a guest list. This would also address data protection concerns regarding paper guest lists. In order to improve the user interface of the contact-tracing app, the authors consider the greater use of defaults for responsible behaviour as well as an optimised provision of information on risk encounters as possible effective measures. Instead of having to actively share a positive test result in the app, this could also be done automatically, unless the respective user explicitly objects. However, adequate information about risk encounters can only be provided if the success of the app can be measured reliably and the risk assessment is being continuously improved. This could also be optimised with the help of the living laboratory.

For the establishment of the living lab, it is important to obtain a representative population sample of several tens of thousands of persons who would be contacted about participating in the lab. As part of the experiment, the coronavirus contact-tracing app should be expanded to include test functions that could only be activated for participants.