“Pretty Much Every Other Mainstream App Collects More Sensitive User Data”

Questions & AnswersQ&A with ZEW Economist Dominik Rehse

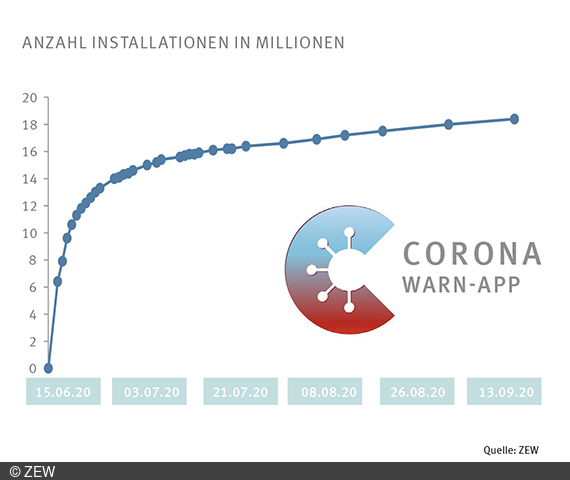

According to information provided by the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), the coronavirus contact-tracing app has been downloaded more than 18 million times. In light of the rise in infection rates, there is hope that the app will facilitate the tracking of chains of infection in the cold winter months ahead and that it will help to control outbreaks of the virus.

In the following interview, Dr. Dominik Rehse, head of the Junior Research Group “Digital Market Design”, speaks about how the app has performed up until now and what is needed in order for it to be effective in protecting individuals from infection.

How can an app save lives?

The contact-tracing app should accelerate the tracking of transmission of the virus. In the case that a user tests positive for having the virus, they can alert the app of this positive test. The following day, other users of the app who have been in very close contact with this person over a relevant period of time in the past two weeks will then be notified that they have been exposed to the virus. Responsible users should then self-isolate and get themselves tested for the virus. By doing so, chains of infection can be broken, which potentially saves lives.

Is the German contract-tracing app a success?

Unfortunately, the app was not released until mid-June and therefore was too late in playing a role in managing the first wave of infection. It could, however, have a greater importance when infection rates increase again in autumn and winter. In any case, a widespread use of the app will be critical. The number of app installations initially grew strongly, but has levelled off since then. Beyond installation rates, it is not possible to say much about the success of the app, as of yet.

Why is that so difficult?

The app was developed with a very strong focus on addressing privacy concerns. Unfortunately, this has had negative consequences regarding the performance measurement of the app. For instance, it cannot be precisely determined how many users have actually notified the app of an infection and how many of the contacts exposed to the virus were then tested. It is also not possible to check how reliable the categorisation as an individual having been exposed to the virus is. The latter is particularly unfortunate, as the Bluetooth technology used for measuring distance was not developed for this purpose and the reliability can, therefore, only be tested under laboratory conditions. Improvements of the distance-measuring algorithm are restricted by the lack of data from day-to-day use of the app.

How did it get to this?

Public debate on the development and release of the contact-tracing app was dominated by sticking points concerning data protection. Political decision-makers involved were apparently guided by these concerns when it came to designing the app’s functionality. This has resulted in an app which most likely exceeds legal data protection requirements by far. Pretty much every other mainstream app collects more sensitive user data, and usually in accordance with prevailing data protection laws. Apart from data protection aspects, hardly any other considerations seem to have found their way into the design of the app. For example, the involvement of local health authorities, who are actually in charge of contact tracing and breaking chains of infection, could have improved the effectiveness of the app. These authorities are informed about every positive test result anyway.

How can the app succeed in getting more people to use it?

So far, the dissemination strategy of the app was limited to advertising through traditional communication channels and organisations with a strong public voice, such as football associations. The downward trend in the number of individuals newly installing the app shows, however, that this strategy also has its limitations. A sensible addition could, for example, be if the contract-tracing app comes pre-installed on new mobile phones or if there were specific incentives for getting more users on board. Incentives should of course not crowd out intrinsic motivation. However, if the app is to become more widely distributed, then additional approaches for its dissemination will have to be systematically tested. The adoption of digital key chains, which solely have the contact-tracing app installed on them, should also be taken into consideration. These could be made available to members of the public who do not own an up-to-date mobile phone and would otherwise not be able to use the app.